A Folded Reality

The Online Experience

Concept and Creation

The Foundling Hospital was Britain’s first residential home for children whose parents could not care for them. Between 1739 and 1954, the Foundling Hospital cared for 27,000 children. Since then, as the children's charity Coram, we have continued to create better chances for children.

In Coram's textile art project, the group of care-experienced young people explored the themes of bedtime, sleep, and dreams. They imagined the Foundlings' thoughts and feelings as they went to bed in their dormitories.

The project was part of Coram's Voices Through Time: The Story of Care programme, made possible by the National Lottery Heritage Fund.

At the Foundling Hospital, children learned a variety of textile skills, such as sewing, knitting, mending, spinning, and weaving.

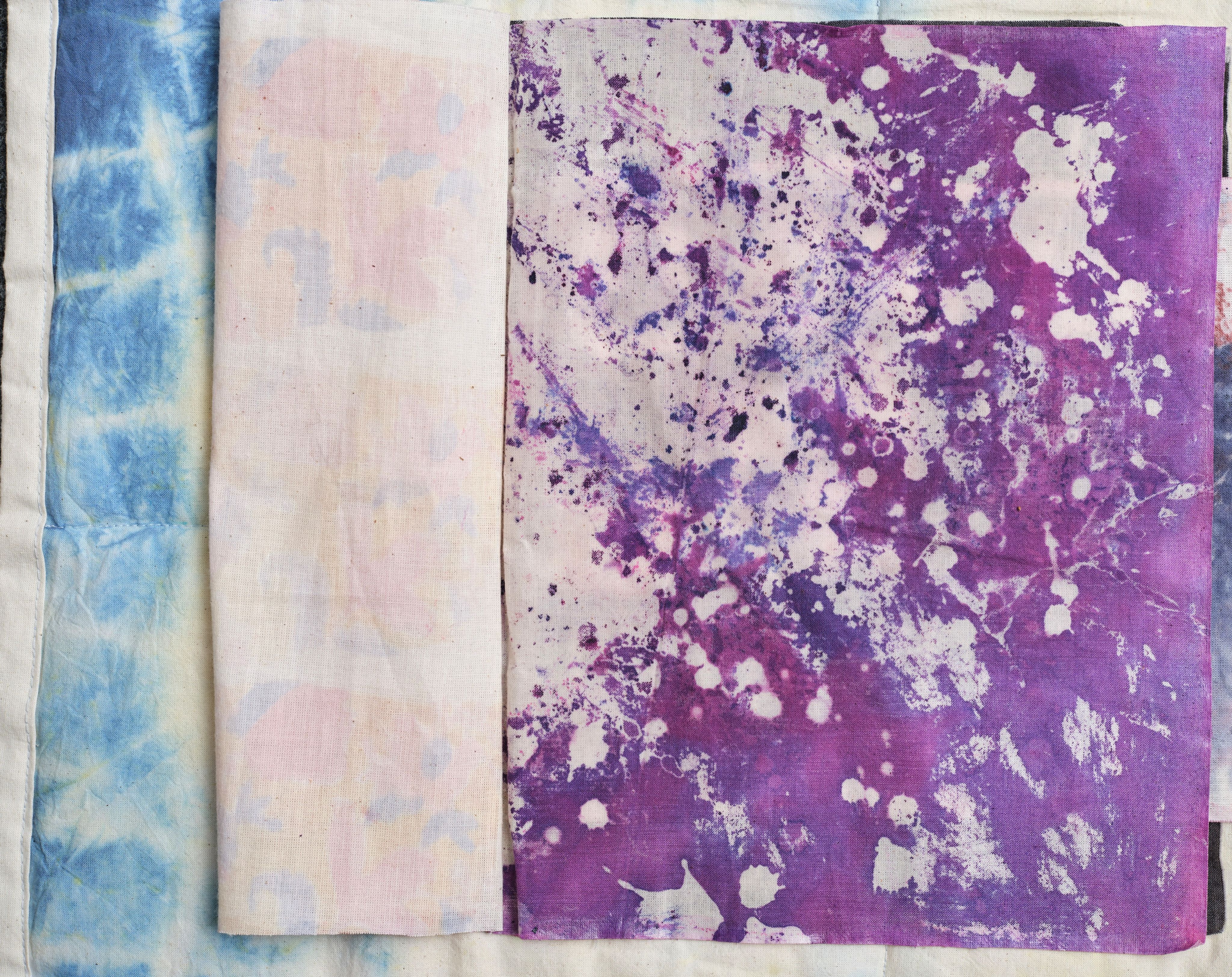

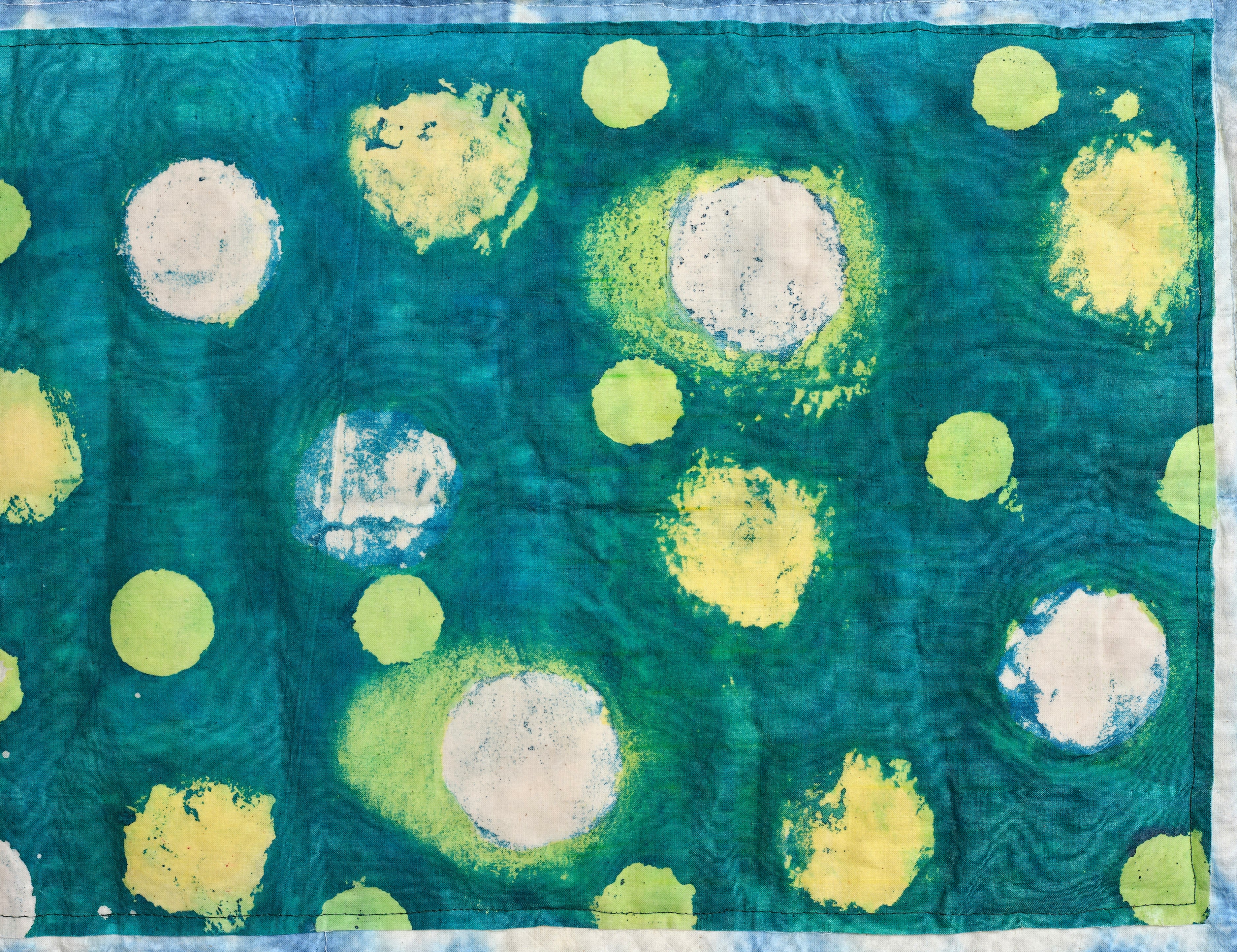

In Coram's textile art project, the care-experienced young people learned how to use batik, shibori and heat-transfer dyeing techniques to create vibrant, illustrated panels.

In the spirit of craftivism, each young person created one or more panels. The 15 panels were then sewn in layers onto the larger, blanket-size back panel.

The artwork is called 'A Folded Reality' because the panels are folded back, one at a time, to reveal hidden realities.

In preparation for designing their panels, the artist-makers kept dream diaries and wrote short poems.

They also drew on their own experiences of the care system to imagine the Foundlings’ dreams and feelings – enabling the blanket to reflect the past through the present.

We invited Story of Care Ambassadors Angie and Ben to discuss the blanket and what it reveals about Foundlings' lives. Here's what they said:

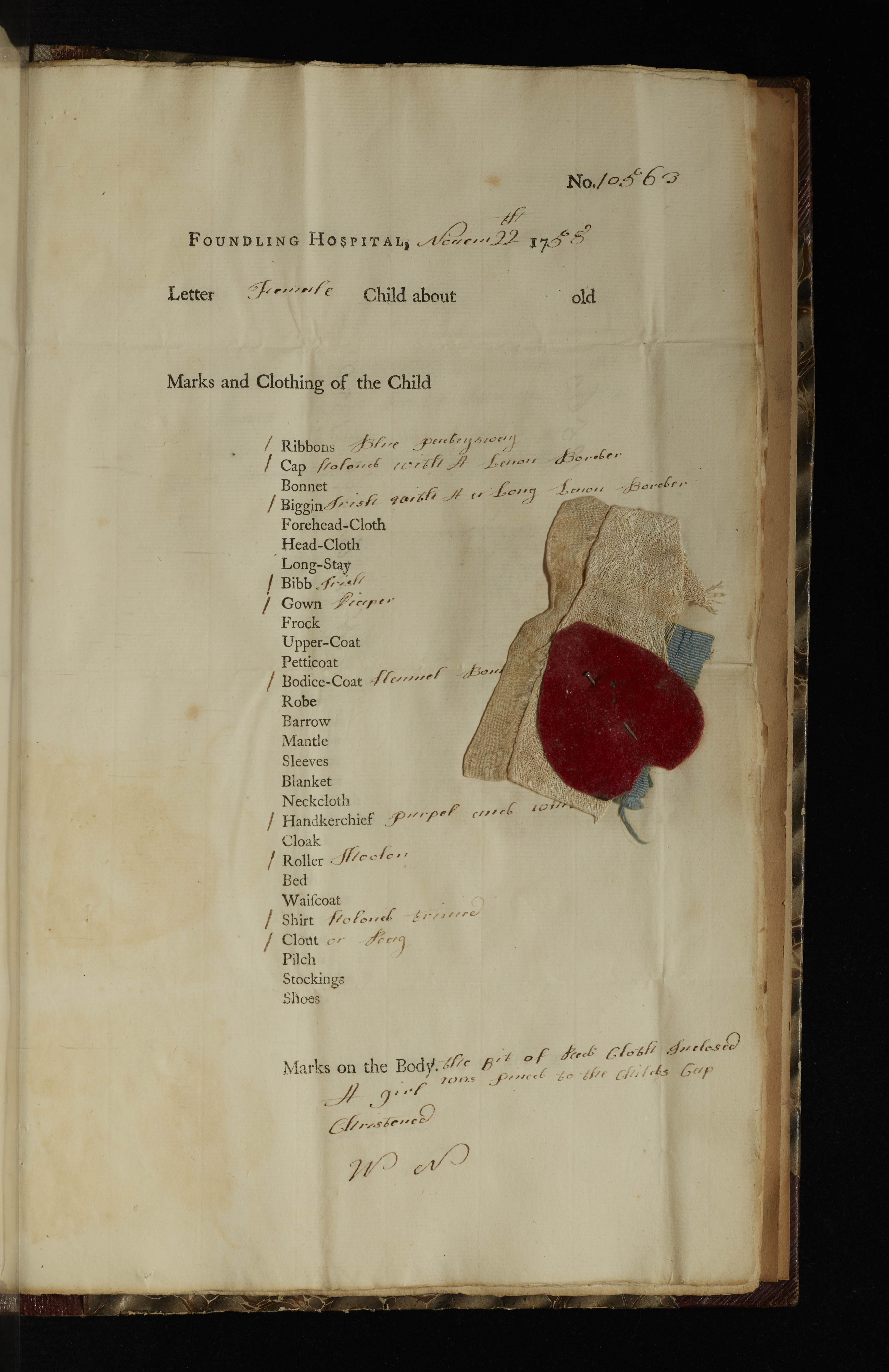

Billet for Foundling Number 10563 (CFH/A/09/001/118/141)

Billet for Foundling Number 10563 (CFH/A/09/001/118/141)

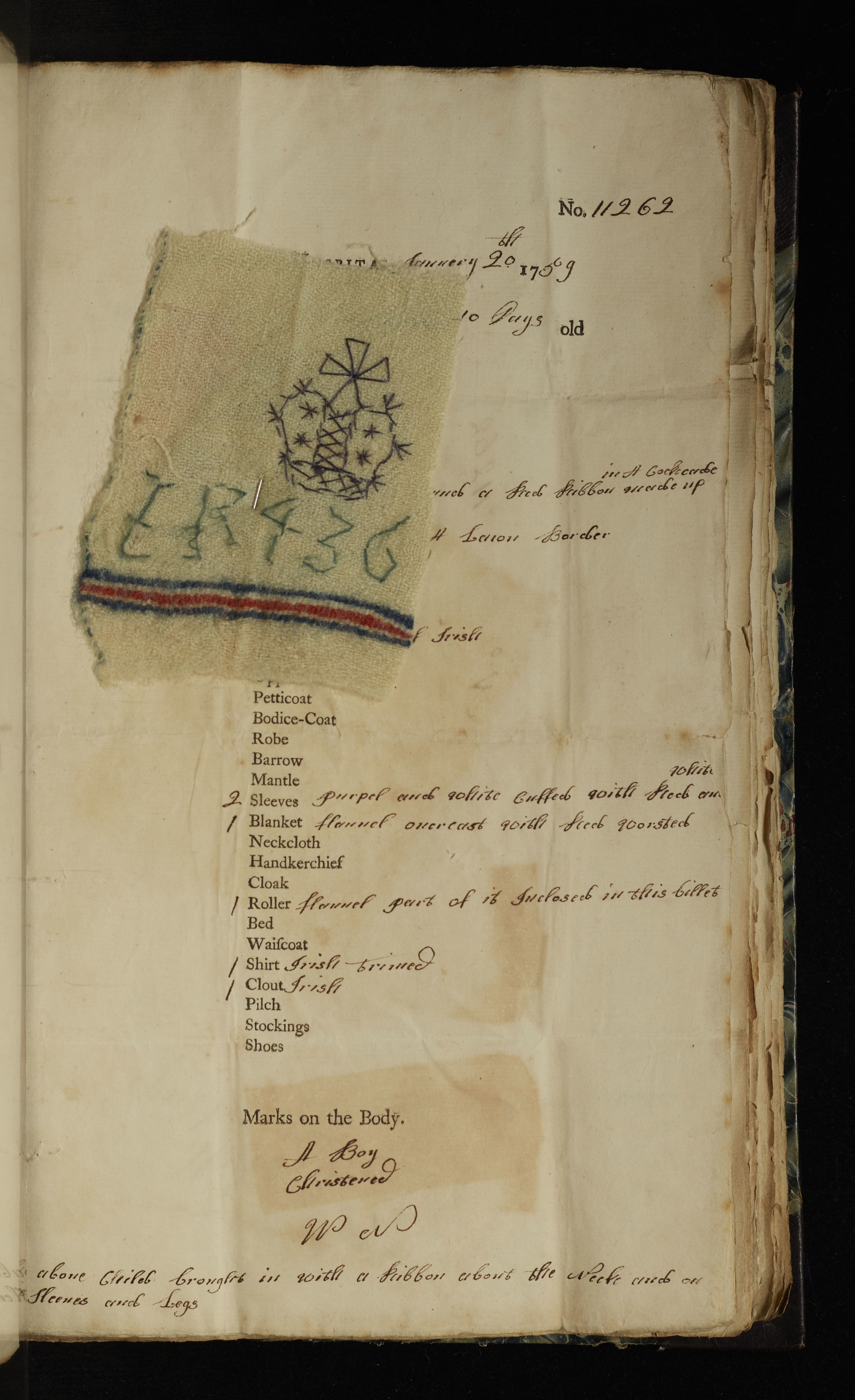

Billet Sheet for Foundling Number 11262 (CFH/A/09/001/126/129)

Billet Sheet for Foundling Number 11262 (CFH/A/09/001/126/129)

Fabric heart and floral pattern token for Foundling Number 13797 (CFH/A/09/001/153/037)

Fabric heart and floral pattern token for Foundling Number 13797 (CFH/A/09/001/153/037)

Blanket panel inspired by the heart tokens

Blanket panel inspired by the heart tokens

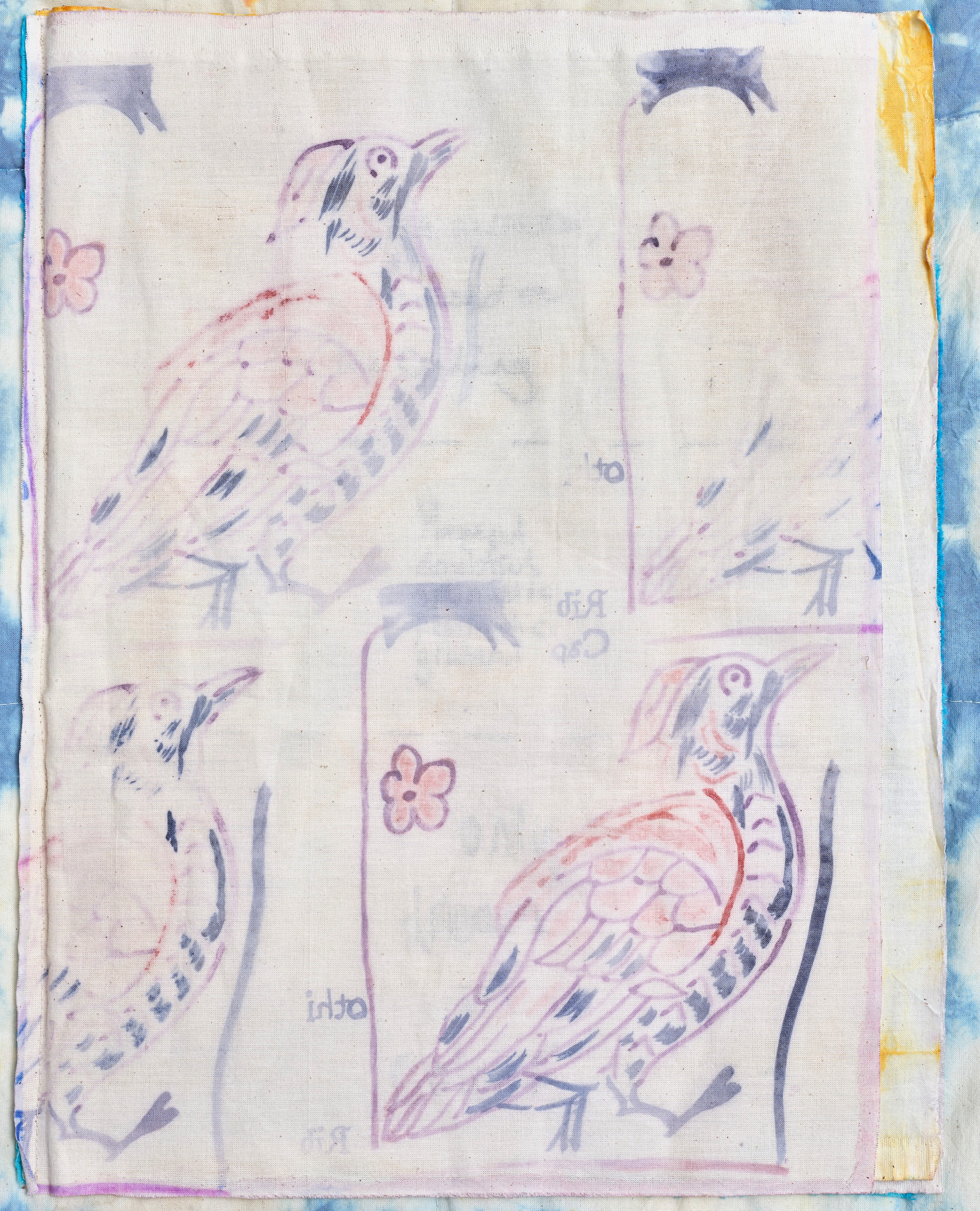

Billet for Foundling Number 13476, with bird fabric (CFH/A/09/001/149/136)

Billet for Foundling Number 13476, with bird fabric (CFH/A/09/001/149/136)

Blanket panel inspired by the bird fabric left for Foundling Number 13476

Blanket panel inspired by the bird fabric left for Foundling Number 13476

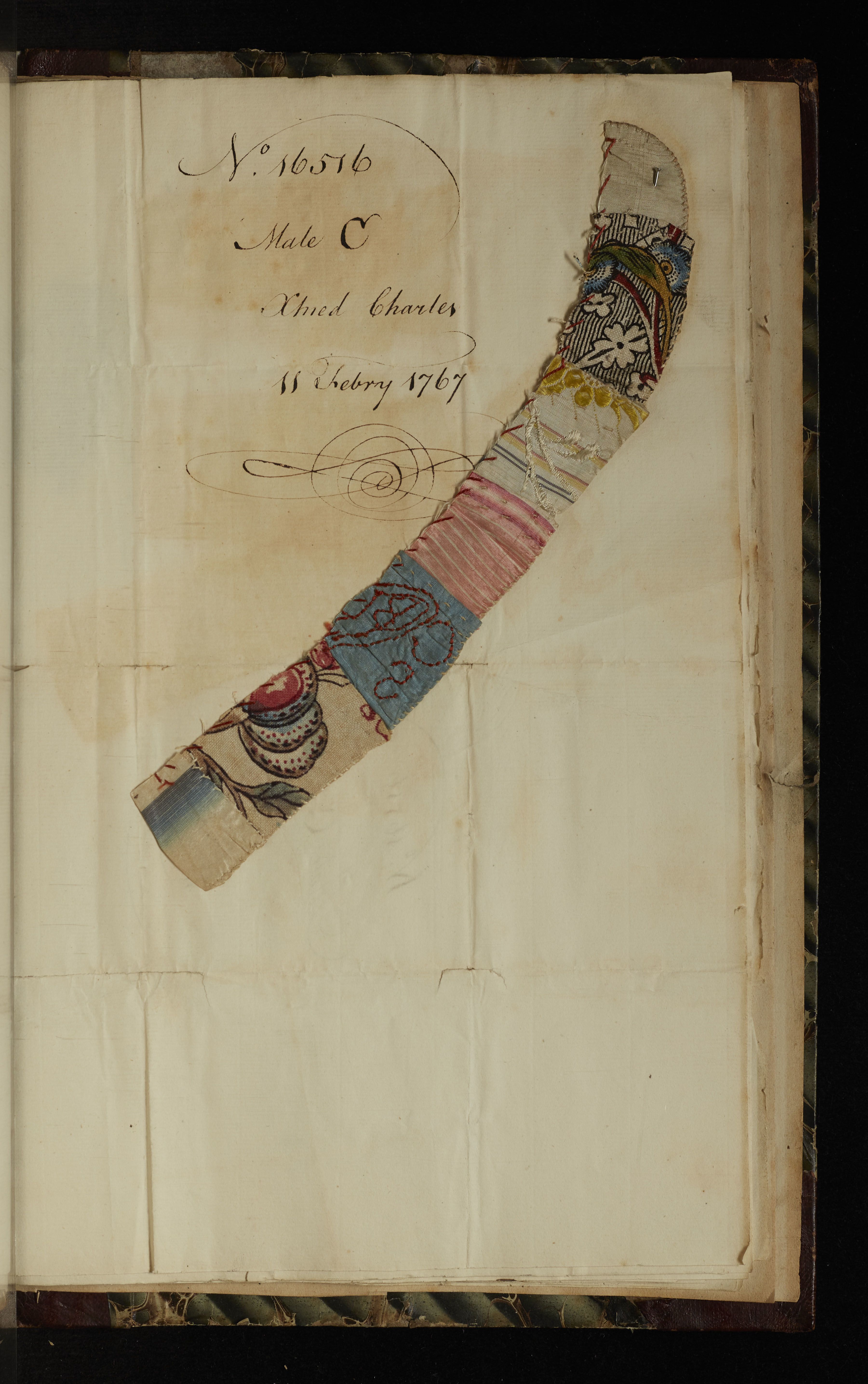

Billet for Foundling Number 16516 (CFH/A/09/001/179/237)

Billet for Foundling Number 16516 (CFH/A/09/001/179/237)

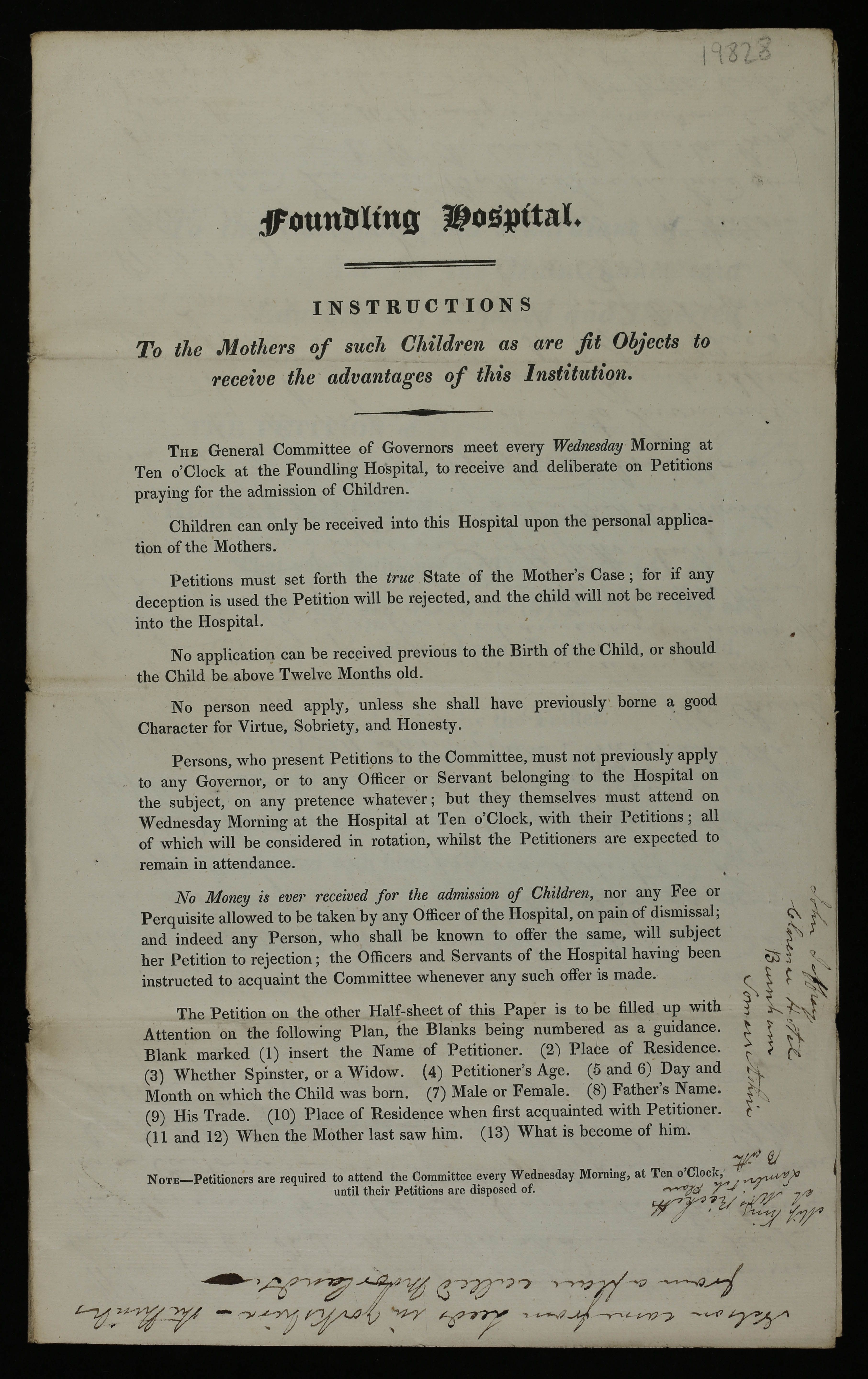

The Billet Sheets

The construction of the blanket was inspired by the 18th-century billets in Coram’s Foundling Hospital Archive.

The billet sheet was a form that recorded key information about a child on the day they were admitted into the Foundling Hospital, such as their sex and approximate age. The billet also recorded the items they arrived with, such as their clothes.

Most of the Foundlings were illegitimate and handed in by their mothers. Often, their mother tied a token or note to their clothes or wrist as a parting memento.

The billet sheets were folded around the tokens and notes in order to keep them secure. In the 19th century, the billets were unfolded, and the tokens and notes pinned to the sheet.

Tokens were often textiles, such as ribbons and pieces of fabric. Several of the panels in 'A Folded Reality' – such as the heart and bird panels – were taken directly from tokens within the Billet Books.

Tokens were a way to reunite Foundlings with their parents, if they ever came back to claim their child. The Foundling Hospital would ask the parents to describe the token and the clothes the child had been wearing.

The tokens symbolise a lasting emotional link between mother and child, made more evocative by the knowledge that the Foundling would never see the token their parent had left for them. The token remained a hidden reality, folded away inside the billet.

Bedtime at the Foundling Hospital

Children were admitted as babies to the Foundling Hospital and immediately sent to live with a wet nurse and her family in the countryside. Then, around age five, the children returned to the Hospital to begin their education. There, they slept in long dormitories within a huge, echoing building.

In the textile art project, the artist-makers imagined the Foundlings folding down their bed sheets and unfolding their nightgowns. They reflected on what the Foundlings missed at bedtime: snuggling up to hear a bedtime story and being tucked in with a kiss.

The Foundlings' blankets were made of coarse wool, not the soft calico of 'A Folded Reality'. The art blanket was made to be touched and explored, drawing attention to the Foundlings' lack of physical and emotional connection at bedtime.

Night time in the dormitories held the potential to be lonely and scary. Several of the blanket's panels imagine the thoughts and feelings of the Foundlings at night.

With no understanding of the importance of emotional nurture (a modern concept), Hospital staff gave little priority to providing the children with comfort at bedtime.

Social historian Carol Harris explains more here:

Bedtime from a Foundling's Perspective

This panel from the blanket suggests what a Foundling may have felt at bedtime: 'Nightmares all of the time, strange noises ... Dreams and nightmares alike, stay'.

A comprehensive account of a Foundling’s life is Hannah Brown's autobiography, The Child She Bare (1918). Below, Coram's archivist, Beck Price, reads Hannah's descriptions of her bedtime experiences at the Hospital.

Explore more of the hidden realities created by the artist-makers below

Panel: 'Lie awake, focussed on the ceiling, hopeful, doubtful, optimistic, pessimistic - I only dream in colour'

Panel: 'Lie awake, focussed on the ceiling, hopeful, doubtful, optimistic, pessimistic - I only dream in colour'

Panel: 'And another child sleeps here – the escape of peace of mind – wonder what will happen next'

Panel: 'And another child sleeps here – the escape of peace of mind – wonder what will happen next'

Panel: 'The night ends when the sun rises, but dreams lost forever - eyelashes sticking with the wonder of what I miss most - floating, loneliness, numb, Human'

Panel: 'The night ends when the sun rises, but dreams lost forever - eyelashes sticking with the wonder of what I miss most - floating, loneliness, numb, Human'

Panel: 'Why does nobody care about me?'

Panel: 'Why does nobody care about me?'

Panel: Two figures with multiple 'Ha Ha' in the background

Panel: Two figures with multiple 'Ha Ha' in the background

Textiles at the Foundling Hospital

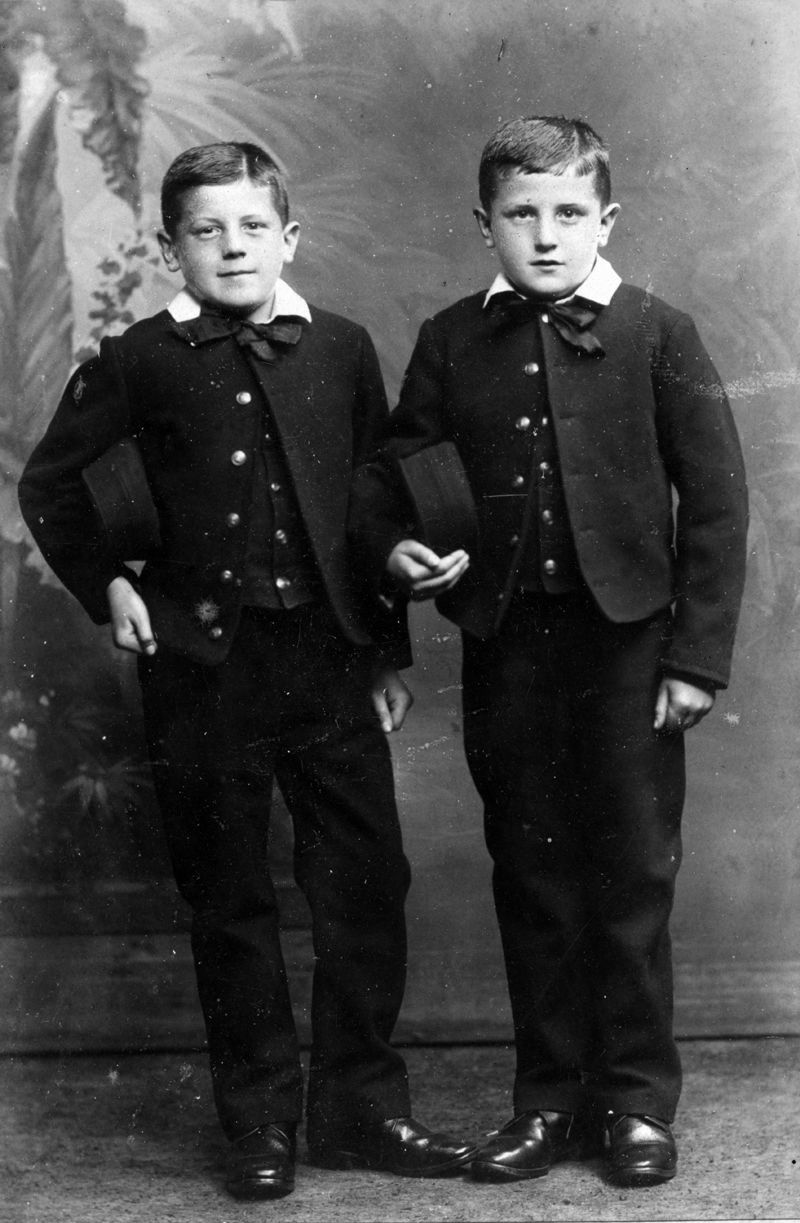

Textiles were a key part of a Foundling's vocational education, with both boys and girls expected to produce clothes and other textiles for the use of the Hospital.

Girls were taught sewing, knitting, spinning, and weaving. Records in Coram's Foundling Hospital Archive contain descriptions of them spinning wool and silk.

Boys are recorded spinning hemp and making fishing nets. Boys also learned to mend clothes and knit socks (known as 'stockings').

The items the Foundlings made were worn by the children themselves or sold to provide funds for the Hospital.

While at the Hospital, the Foundlings wore uniforms. These were modeled on the work they would likely be doing as their future employment. Social historian Carol Harris explains:

Girls sewing in the grounds of the Foundling Hospital, early 20th century

Girls sewing in the grounds of the Foundling Hospital, early 20th century

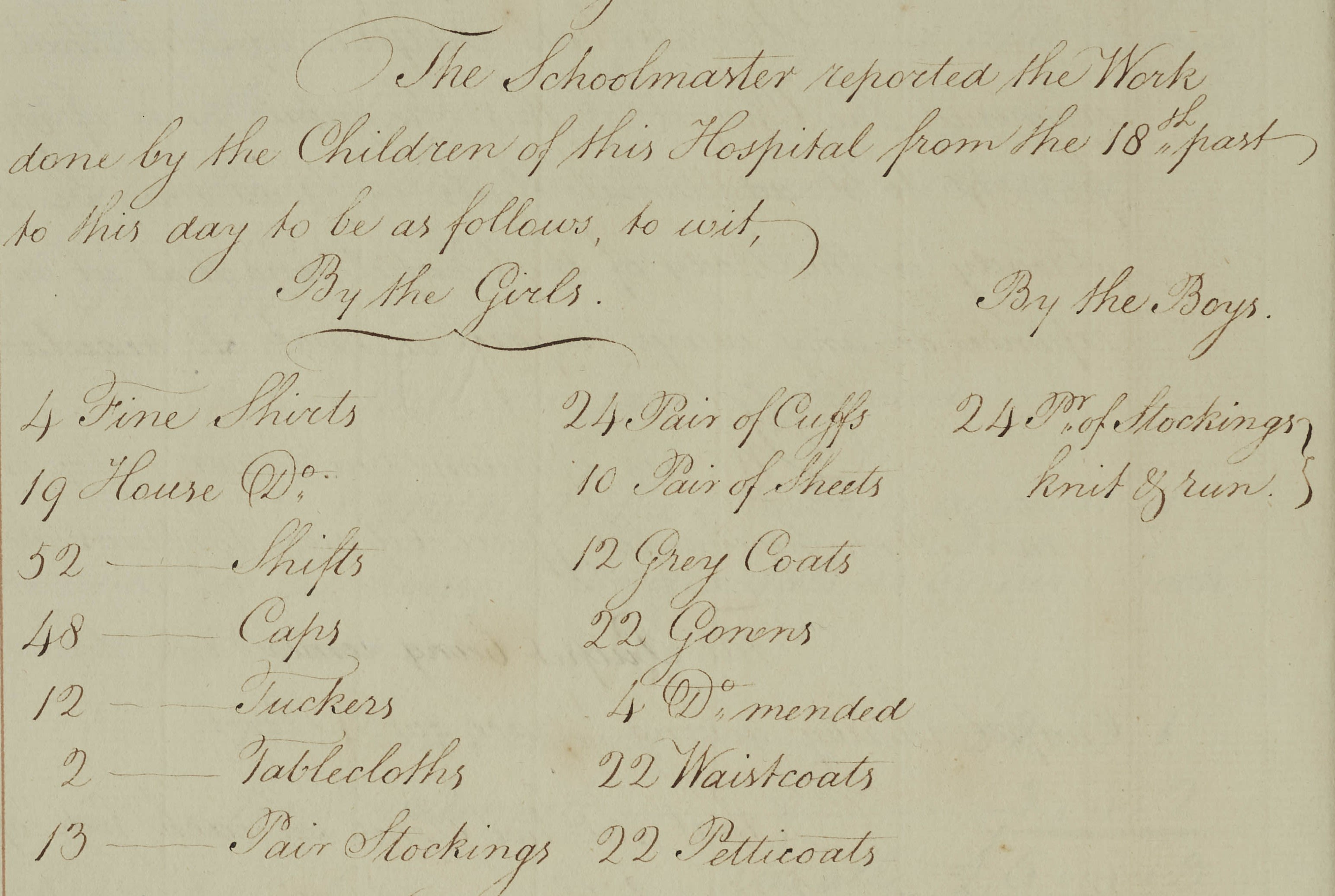

The Sub-Committee minutes for 4 March 1786 listed the clothing the Foundlings had made since 18 February (CFH/A/03/005/018/250)

The Sub-Committee minutes for 4 March 1786 listed the clothing the Foundlings had made since 18 February (CFH/A/03/005/018/250)

The Sub-Committee minutes for 4 March 1786 listed the clothing the Foundlings had made since 18 February (CFH/A/03/005/018/250)

The Sub-Committee minutes for 4 March 1786 listed the clothing the Foundlings had made since 18 February (CFH/A/03/005/018/250)

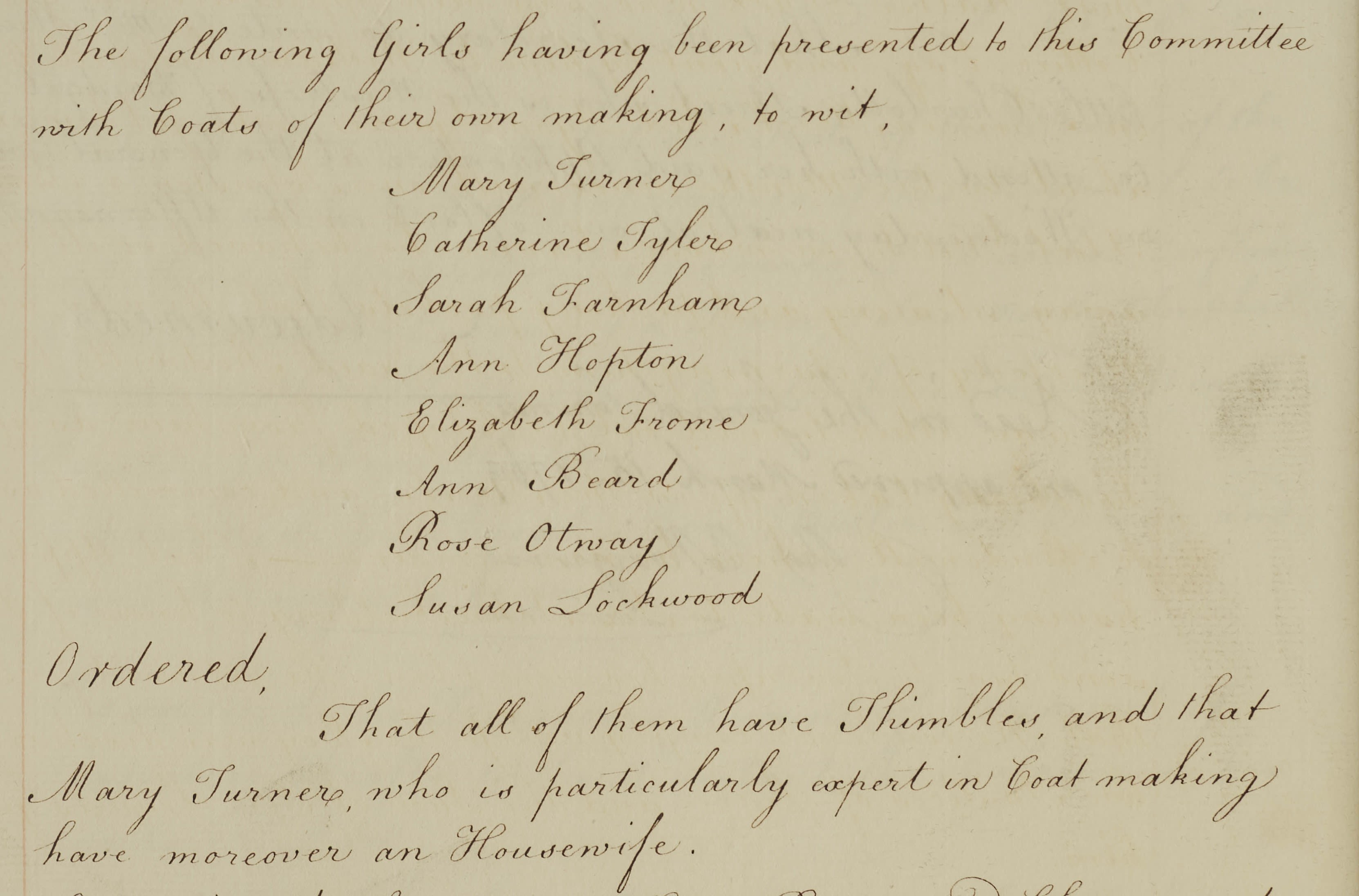

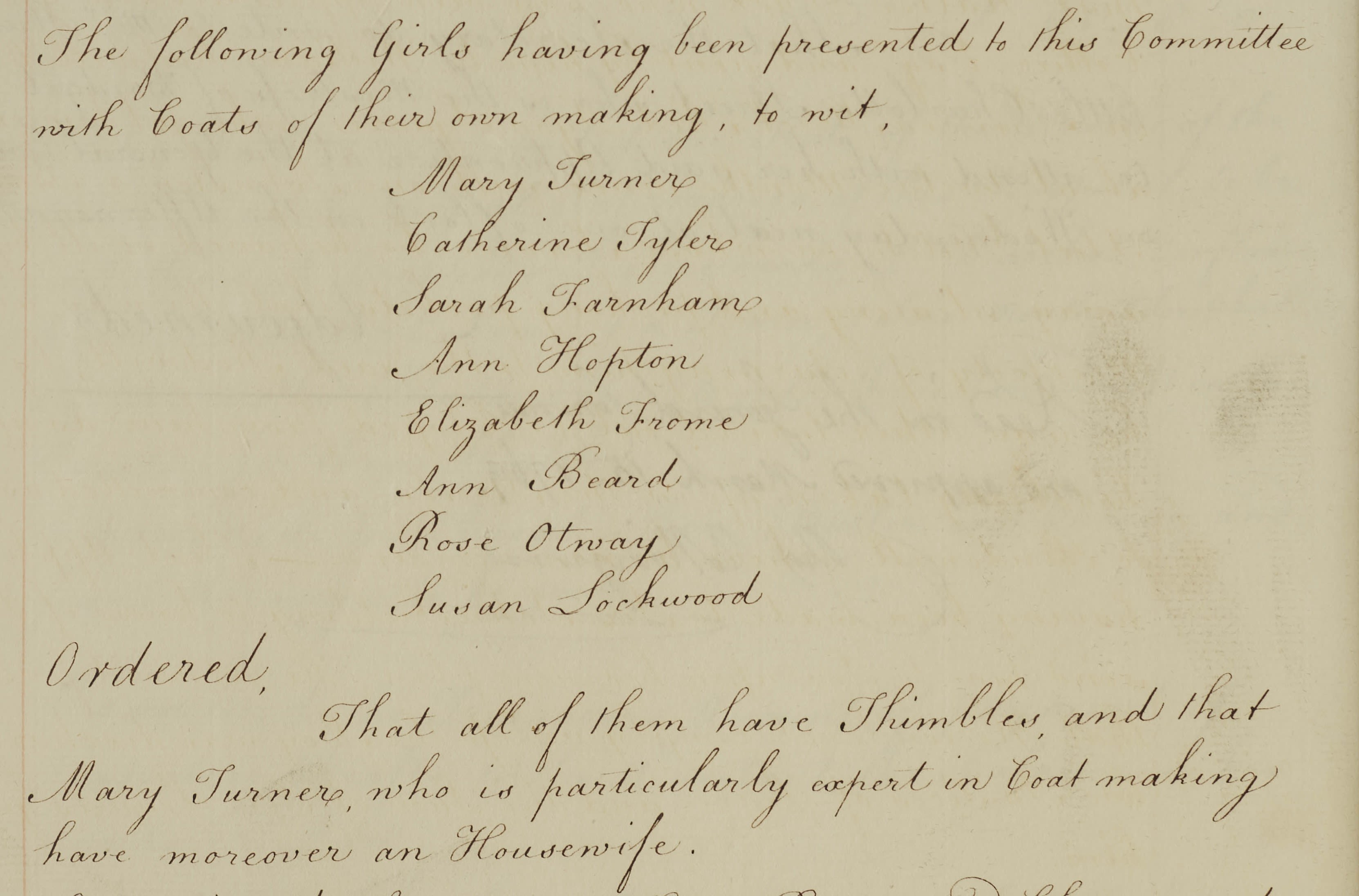

The Sub-Committee minutes for 18 March 1769 listed girls who had made coats. They all got a silver thimble as a reward; one received a sewing kit called a 'housewife' (CFH/A/03/005/008/040). Read Rose Otway's story on the Coram Story website.

The Sub-Committee minutes for 18 March 1769 listed girls who had made coats. They all got a silver thimble as a reward; one received a sewing kit called a 'housewife' (CFH/A/03/005/008/040). Read Rose Otway's story on the Coram Story website.

The Sub-Committee minutes for 18 March 1769 listed girls who had made coats. They all got a silver thimble as a reward; one received a sewing kit called a 'housewife' (CFH/A/03/005/008/040). Read Rose Otway's story on the Coram Story website.

The Sub-Committee minutes for 18 March 1769 listed girls who had made coats. They all got a silver thimble as a reward; one received a sewing kit called a 'housewife' (CFH/A/03/005/008/040). Read Rose Otway's story on the Coram Story website.

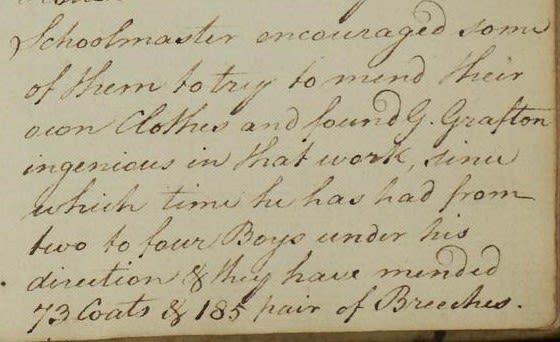

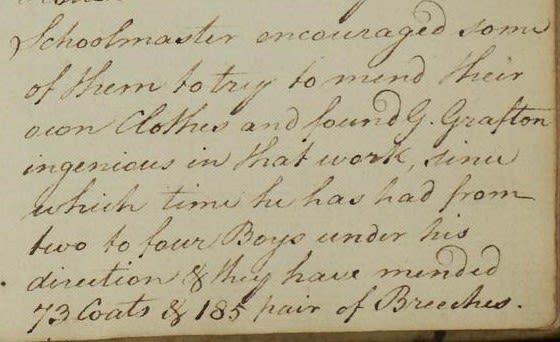

The Sub-Committee minutes for 12 June 1784 noted George Grafton's skill in mending clothes (CFH/A/03/005/017/233). Read George's story on the Coram Story website.

The Sub-Committee minutes for 12 June 1784 noted George Grafton's skill in mending clothes (CFH/A/03/005/017/233). Read George's story on the Coram Story website.

The Sub-Committee minutes for 12 June 1784 noted George Grafton's skill in mending clothes (CFH/A/03/005/017/233). Read George's story on the Coram Story website.

The Sub-Committee minutes for 12 June 1784 noted George Grafton's skill in mending clothes (CFH/A/03/005/017/233). Read George's story on the Coram Story website.

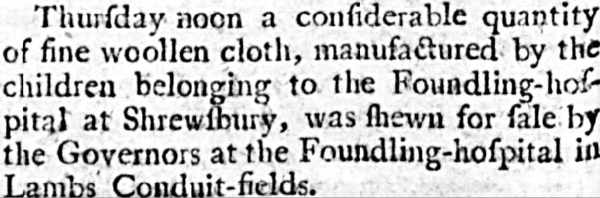

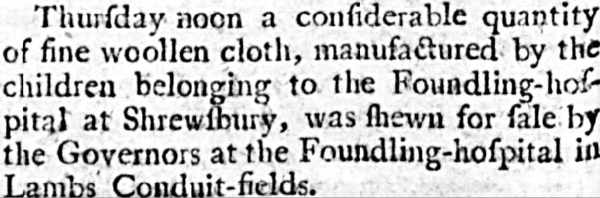

In 1767, the Liverpool Chronicle reported on the sale of 'fine woollen cloth' woven by Foundlings.

In 1767, the Liverpool Chronicle reported on the sale of 'fine woollen cloth' woven by Foundlings.

In 1767, the Liverpool Chronicle reported on the sale of 'fine woollen cloth' woven by Foundlings.

In 1767, the Liverpool Chronicle reported on the sale of 'fine woollen cloth' woven by Foundlings.

Girls of the Foundling Hospital in their uniforms, early 20th century

Girls of the Foundling Hospital in their uniforms, early 20th century

Boys of the Foundling Hospital in their uniforms, early 20th century

Boys of the Foundling Hospital in their uniforms, early 20th century

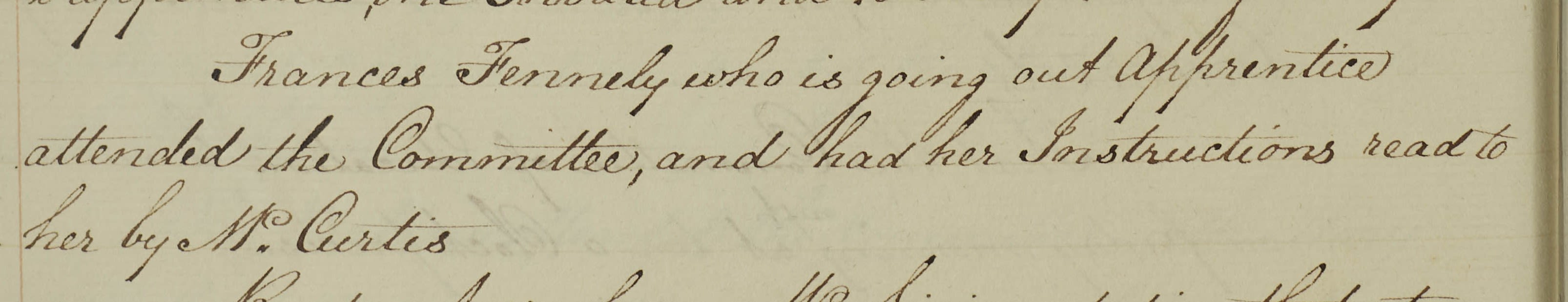

Sub-Committee Minutes detailing Frances Fennely being prepared for her Apprenticeship by Mr. Curtis (CFH/A/03/005/030/054)

Sub-Committee Minutes detailing Frances Fennely being prepared for her Apprenticeship by Mr. Curtis (CFH/A/03/005/030/054)

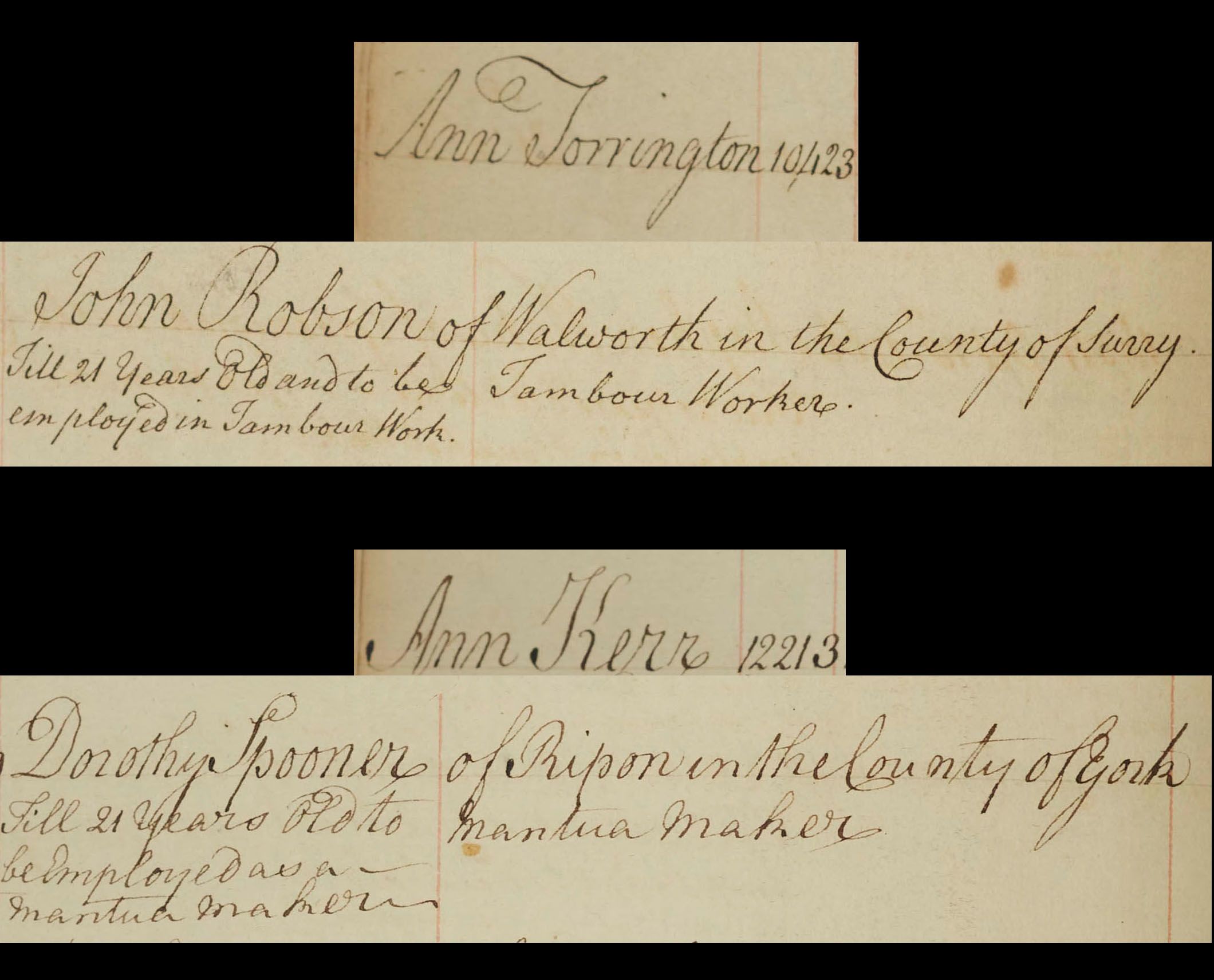

Apprenticeship Register shows Ann Torrington apprenticed in tambour work and Ann Kere apprenticed as a mantua maker (CFH/A/12/003/002/160; CFH/A/12/003/002/112)

Apprenticeship Register shows Ann Torrington apprenticed in tambour work and Ann Kere apprenticed as a mantua maker (CFH/A/12/003/002/160; CFH/A/12/003/002/112)

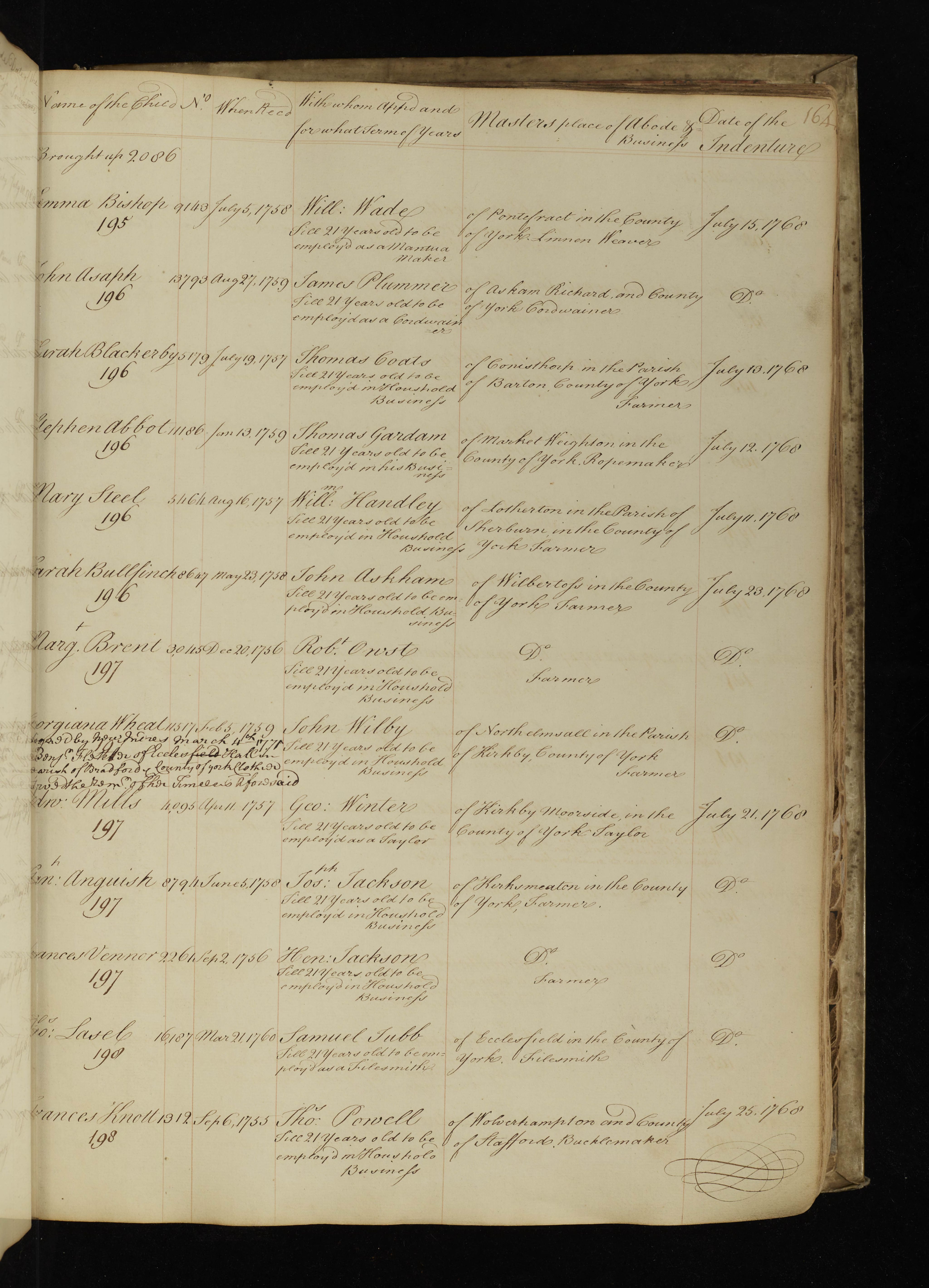

Apprenticeship Register shows Edward Mills apprenticed to a taylor, Stephen Abbot to a ropemaker, and Emma Bishop to a mantua maker (CFH/A/12/003/001/197)

Apprenticeship Register shows Edward Mills apprenticed to a taylor, Stephen Abbot to a ropemaker, and Emma Bishop to a mantua maker (CFH/A/12/003/001/197)

The Foundling Hospital's boys band, 1920s

The Foundling Hospital's boys band, 1920s

Apprenticeships

Between the age of 10 and 16, Foundlings finished their schooling at the Foundling Hospital and started their apprenticeships. These prepared them to make a living as an adult.

Foundlings lived with their apprentice master or mistress, who trained them.

Girls usually went into domestic service. Their duties would often include ‘plain work’ – the mending and fixing of clothes. Some girls learned the trades of tambour embroidery and dressmaking (called 'mantua making').

Boys usually learned a trade or joined a military band. Some boys were apprenticed to tailors and textile merchants.

The apprenticeships offered in 18th and 19th centuries were shaped by class expectations. The Hospital's aim was to make children 'useful' to society as clerks, tradesmen, labourers, servants and soldiers.

Stigma and Assumptions

Brigid Robinson, Managing Director of Coram Voice, says that today there is still stigma about being in care, which leads to harmful misconceptions.

“How do you describe to other people that you don't live with your family and why? That's often quite difficult. People think that if a child is in care, they've done something wrong - that it's their fault.”

Another misconception is that looked-after children do not achieve as well as their peers. Young people report that others have lower expectations of them. Brigid Robinson says:

“There are over 80,000 children in care, with another 45-50,000 care leavers. Within that group, there is a whole plethora of individuals, each with their own uniqueness. So, to make generalised statements about such a diverse group is unhelpful and can play out negatively.”

To challenge assumptions, young people in care need platforms to use their voice and share their stories, such as Coram's Voices Though Time creative projects.

Robyn, one of the blanket's artist-makers, says:

“Voices Through Time was a community I didn't have, that my local authority didn't provide. Since I've done the project, I'm proud to be a care-experienced person. It allowed me to think of other ways to tell my story and those of others whose voices are lost. The story of care is your own story.”

Brigid Robinson says:

“Hearing the voice of young people from their perspective, with the things that they think are important to talk about, is really powerful. It's an authentic voice, and it is important for us to listen to that. We can learn a lot.”

Foundlings' Voices

Most of the records in Coram's Foundling Hospital Archive are administrative and focused on the operation of the institution. They are written from the perspective of the Governors, the staff, and the apprentice masters and mistresses.

Social Historian Carol Harris talks about the absence of Foundlings' voices in the archive:

But the archive does give us glimpses into individual Foundlings' lives, as told in their own words. For instance, the archive contains many letters from Foundlings to Hospital staff written during and after their apprenticeships.

It also has letters from Foundlings requesting assistance in later life. The Hospital was responsible for the Foundlings until they turned 21 and finished their apprenticeship. But the Hospital continued to offer assistance from its Benevolent Fund if they encountered difficulty as adults.

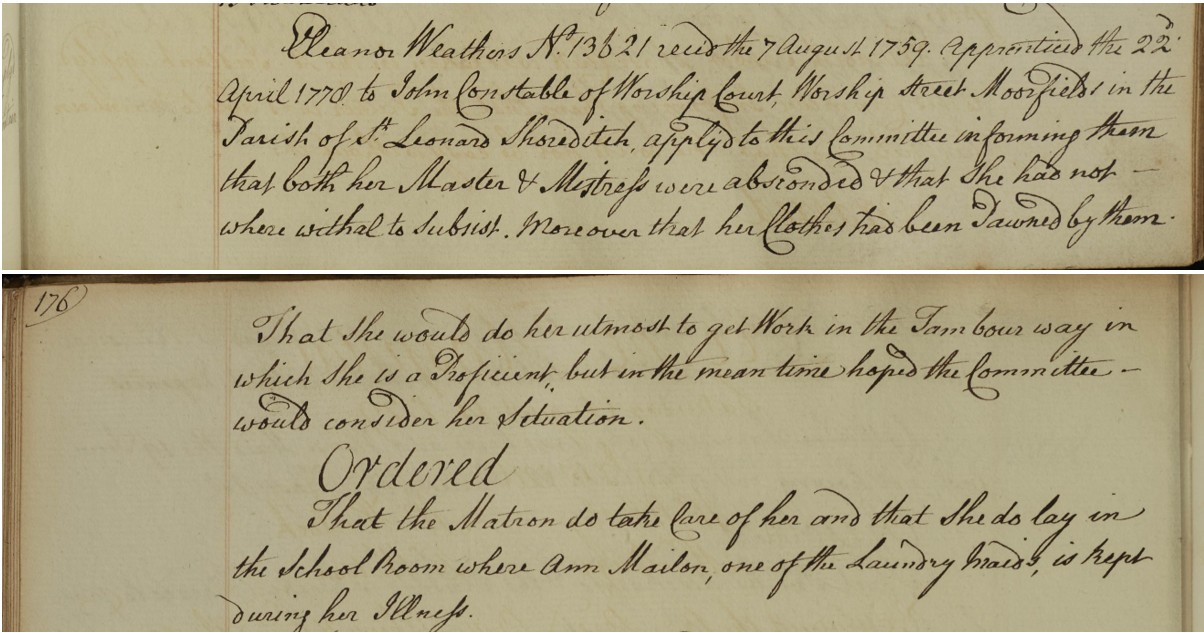

In 1779, Foundling Eleanor Weathers wrote to the Governors after her apprentice master and mistress abandoned her and pawned all her clothes. The Foundling Hospital took Eleanor back in until another apprenticeship could be found.

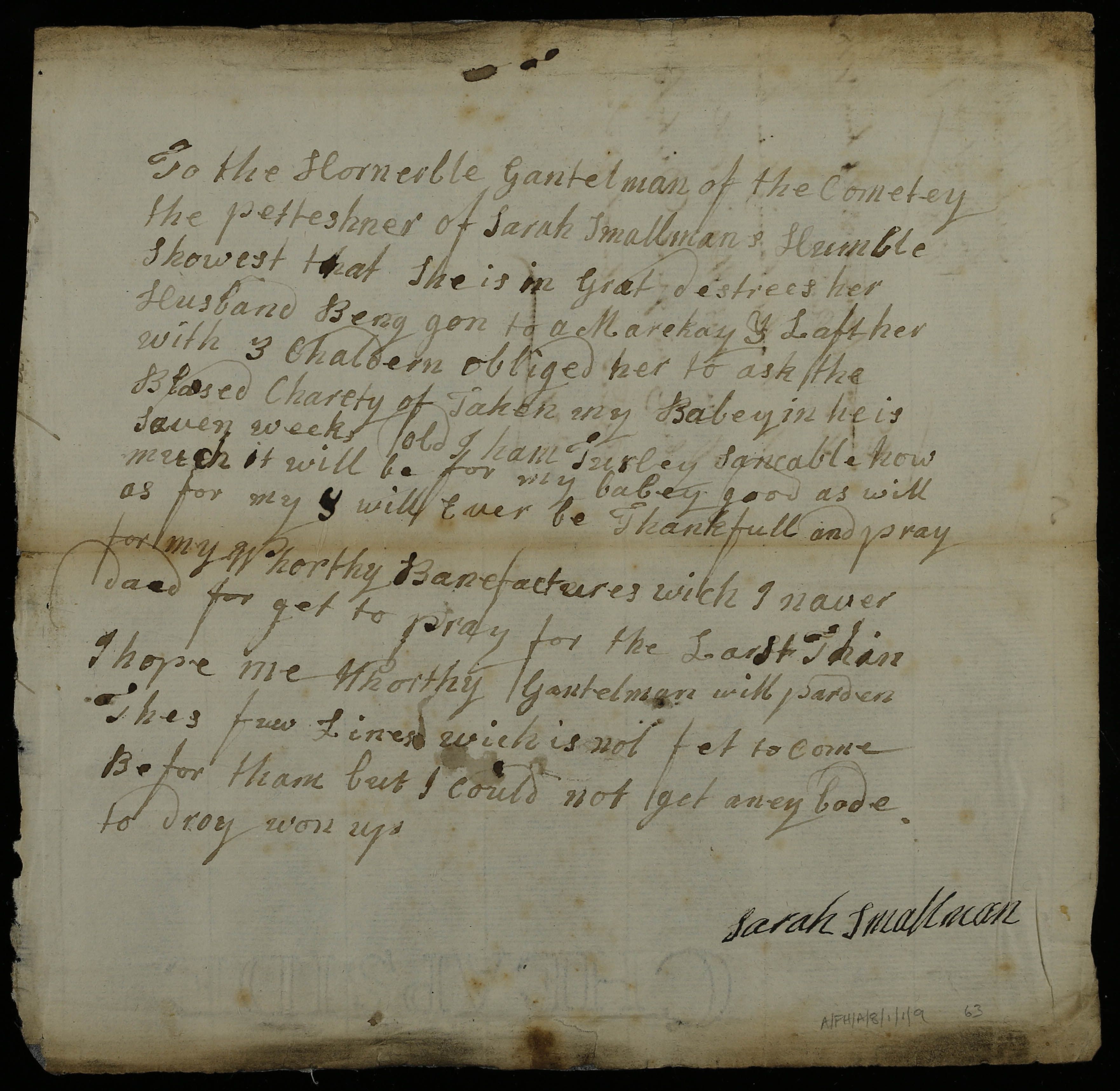

In 1778, Foundling Sarah Smallman wrote to the Hospital when her husband left her and their three children. She asked for her seven-week-old baby to be admitted to the Hospital, and he was. Her child was named George Prescott (No. 17352) by the Foundling Hospital and was claimed back by Sarah the next year.

In the 1850s, Foundling Augustus Browne regularly corresponded with Hospital staff during his time in the British Army. The archive's collection of his letters are an important historical record of the Crimean War.

The archive provides limited insights into the lived experience and opinions of the Foundlings. Therefore, Coram's Voices Through Time programme has aimed to tell their individual stories - to give them a voice. In our creative projects, care-experienced young people have imagined Foundlings' thoughts and feelings, filling in the gaps in the archival record.

Sub-Committee Minutes detailing Eleanor Weathers' request for assistance from the Foundling Hospital (CFH/A/03/005/014/205-206). Read Eleanor's story on the Coram Story website.

Sub-Committee Minutes detailing Eleanor Weathers' request for assistance from the Foundling Hospital (CFH/A/03/005/014/205-206). Read Eleanor's story on the Coram Story website.

Former Foundling Sarah Smallman's petition letter (CFH/A/08/001/001/009/063/a1)

Former Foundling Sarah Smallman's petition letter (CFH/A/08/001/001/009/063/a1)

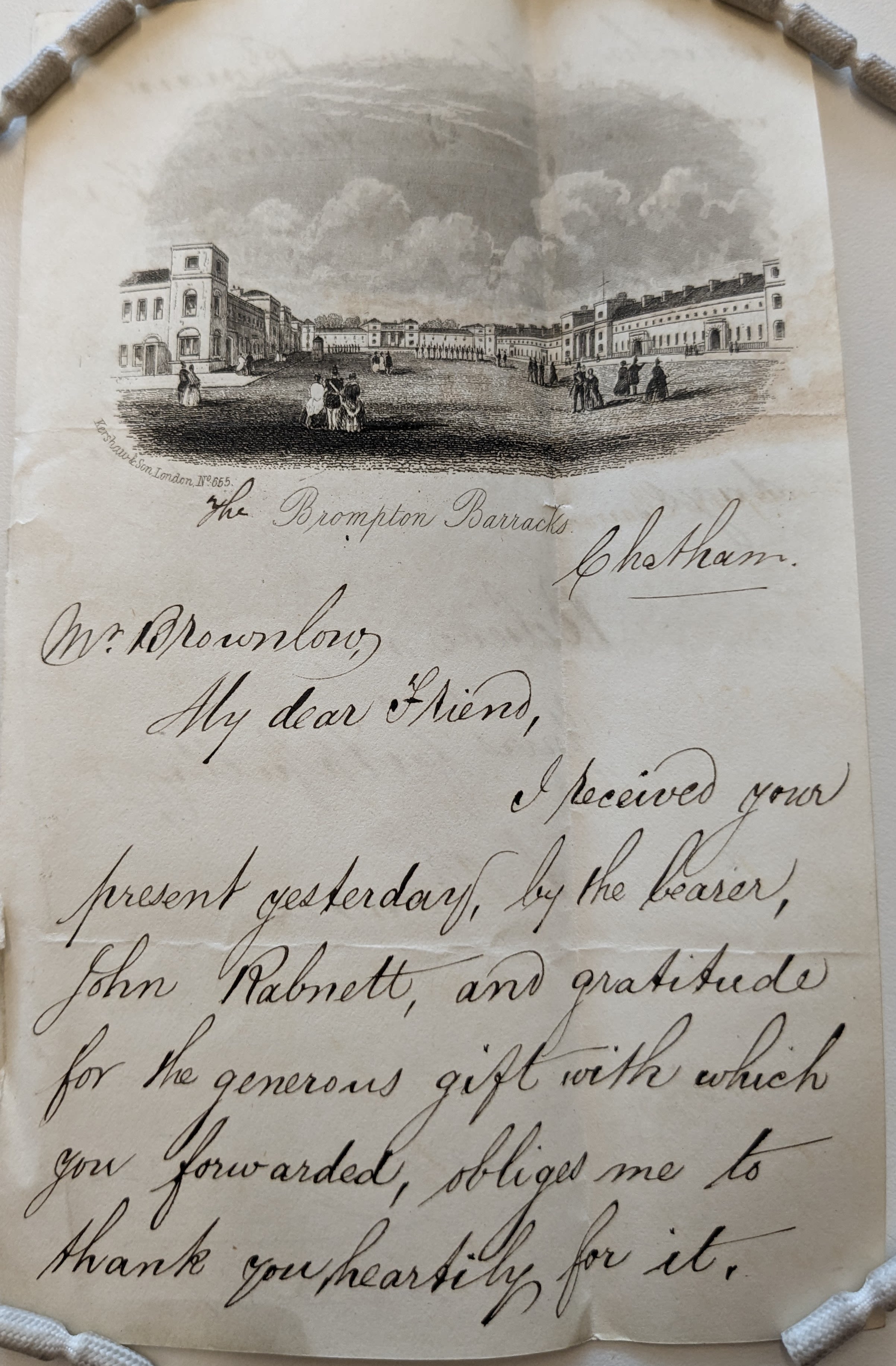

Letter from Foundling Augustus Browne to John Brownlow, Secretary of the Foundling Hospital (CFH/A/06/001/112/002)

Letter from Foundling Augustus Browne to John Brownlow, Secretary of the Foundling Hospital (CFH/A/06/001/112/002)

The Future of Care

Robyn, one of the blanket's artist-makers, produced the panel called ‘Dream House’. It captured a future dream in which Robyn lives in a house with the blanket's other creators who had become her friends.

Robyn explained her making process:

“I traced the house onto the material and went over it with hot wax so the colours stayed where I wanted them to go. Then I did colour science, mixing the oil and the water together to get the right shades. I included all our favourite colours – somehow I happened to have every single colour and just went for it.”

Her panel depicts a home life surrounded by others who have an understanding of the care system. Life would consist of “games, parties, food fights, like a massive slumber party type thing”.

Inspired by Robyn’s panel, Story of Care Ambassadors Angie and Ben shared their aspirations for an improved care system:

Brigid Robinson shared her thoughts about the future of the care system:

“I would want a care system that enables young people to thrive into adulthood, that gives them the support they need to do that.”

“The crux of it is that our expectations of children and young people in care should be as positive as they would be if they were our children. The question is: if this were your child, would it be good enough? And if the answer to that question is no, then we shouldn't be doing it.”

We asked Story of Care Ambassador Angie what panel she would add to the blanket. Here is what she said:

What panel would you add?

Voices Through Time: The Story of Care

The textile art project, called A Stitch in Time, was one of the creative projects for care-experienced young people in Coram's Voices Through Time programme. Coram partnered with the Foundling Museum to deliver it.

In the Voices Through Time programme, Coram digitised 23% of its vast Foundling Hospital Archive. The creative projects uncovered the Foundlings' stories within the digitised records in order to bring the past to life.

Read Foundlings' stories and view more Voices Through Time projects on the Coram Story website.

Voices Through Time: The Story of Care was made possible by the National Lottery Heritage Fund.

About Coram

Coram is a vibrant charity group of specialist organisations, working tirelessly to create better chances for hundreds of thousands of children and young people each year.

The charity champions children’s rights and wellbeing, making lives better through legal support, advocacy, adoption, and a range of therapeutic, educational and cultural programmes.

All of Coram’s work delivers across seven key outcomes for children and young people: a fair chance, a loving home, a voice that’s heard, a chance to shine, skills for the future, no matter where and a society that cares. Find out more on our website.

Copyright © Coram. Coram licenses the images of the blanket and the text under Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 (CC BY-NC).